Film Review: Letters From Baghdad

LETTERS FROM BAGHDAD(2017) DIRS. ZEVA OELBAUM, SABINE KRAYENBÚHL

By Belle McIntyre

“We don’t know exactly what we intend to be in this country. We rushed into this business with our usual disregard for a comprehensive politics scheme. Can you persuade people to take your side when you’re not sure if in the end whether you’ll be there to take theirs?” This was written about the British occupation of Iraq in the early 1920’s by Gertrude Bell, a woman hailed in the British press as “the female Lawrence of Arabia”. How prescient a statement and how timely. It appears that we are still doomed to repeat that behavior today. These are the words of the remarkable subject of this fascinating documentary.

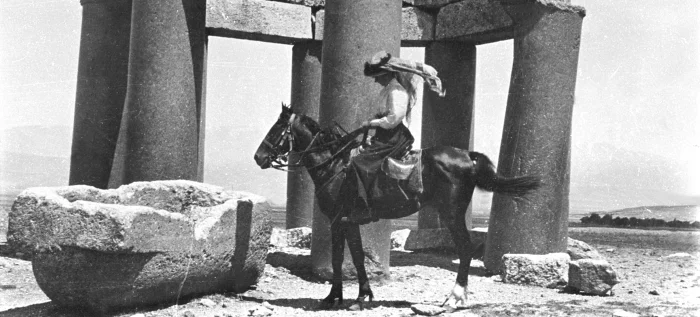

The adventures and accomplishments of Gertrude Bell, a Victorian English aristocrat, who abandoned her comfortable privileged life in Europe to immerse herself in a harsh Arab world in the last quarter of the nineteenth century would be hard to fathom and tempting to doubt were it not chronicled by thousands of letters, official documents and photographs she left behind. A prolific letter writer and photographer, who printed her own images, in what surely must have been hugely challenging conditions. She became instrumental in the geopolitics of the Middle East.

Her intelligence was evident early on when she was the first woman to graduate from Oxford with top honors and a degree in modern history. Shortly thereafter she traveled to visit an uncle who was Ambassador in Tehran and she was irresistibly drawn to the desert and it’s inhabitants. She never looked back and the rest of her life was fully focused on the Middle East. She travelled 1500 miles across the desert on a camel, became fluent in Farsi and Arabic and steeped herself in tribal lore and customs. Her diplomatic connections provided her access to the British colonial elite as well as high level Arabic rulers and tribal leaders. Although, as a woman, she was something of an anomaly, she was nonetheless welcome and moved easily among all of the people/men who were influential in shaping the future of the Middle East at the time. The impact of that is still being felt today for better or worse (arguably worse).

It is odd that she is not better known today as her achievements are impressive. She was engaged by British Intelligence as a spy in 1915. She attended the Paris Peace Conference as a diplomat in 1919. She was invited by Winston Churchill to the Cairo Conference in 1921 and many of her contemporaries considered her the most influential person in the middle east at the time. After her political influence waned she stayed on in Iraq and put her substantial archaeological and anthropological knowledge to use and founded the National Museum of Iraq and was responsible for collecting its contents for preservation and posterity. Tragically and unforgivably, it was looted during the United States invasion of Iraq. She was obviously admired by many at the highest levels. To many others of lesser rank she was regarded with suspicion and distrust and regarded as a nuisance to be endured. Much of that can be attributed to sexism and outright misogyny among the military.

Her story is largely told through her letters, mostly to her beloved father and stepmother, which are voiced by Tilda Swinton, who also co-produced. They reveal a depth of feeling toward them as well as her infatuation with her adopted country. There are also letters from her English friends and family as well as her peers in Arabia which are spoken by actors filmed and dressed like the speakers, such as T.E. Lawrence, Vita Sackville-West, an American missionary, and various military personnel. All of the letters reveal disparate versions of Gertrude.

The portrait that emerges is of a somewhat typical Victorian woman of her class. In photographs she appears stern and unsmiling. She travels with all of the trappings of the period - corsets, long dresses, elegant shoes, hats and gloves. In spite of her warm and affectionate letters home, she comes across to her peers as ungenerous of spirit, reserved, chilly and somewhat priggish. She had two intense unsuccessful love affairs (most-likely unconsummated) with inappropriate men. One of them was deemed unsuitable by her father and the other was married. This fact may have contributed to a seemingly melancholic state of mind. By the end of her life, she felt too changed to go back to England and no longer useful in her chosen country. In 1928 she died of an overdose of sleeping pills, unclear whether intentional or accidental, but enough signals that her enthusiasm for life was waning.

With such an immense amount of archival source material it is perhaps understandable that the film makers were overwhelmed and imagined that it could speak for itself. To be sure the film footage is breathtaking in its immediacy and exoticism. The mass migrations and movements of people is on a grand scale and provides a mesmerizing background for the spoken words. Yet it still feels somewhat flat. It has the fascination and interest of looking at a scrapbook or an exhibition which is more than enough. It is a gratifying, edifying and informative experience. However, I think there has been a missed opportunity to take advantage of the fact that the medium of film affords to provide a unifying narrative to connect the events and give a more vivid context of the historical moment to round out the picture and give it some life. Still, it is well worth seeing. I am just a bit frustrated that I don’t feel that I know Gertrude Bell. My appetite has been whetted and I remain hungry.